Dayuancun is a small village tucked away in high mountains. An old legend has it that about 400 years ago, a middle-aged scholar came to the village after repeatedly failing the imperial examination.

Villagers asked him to stay and teach their children how to read and write. However, the scholar was so piqued by his academic failure that he declined the offer, vowing never to touch a book again. Instead, he planted two gingko trees in front of his house, which grew so quickly that they bore fruits the following year. He drank and slept under the trees all day long. One day, he woke up wild with joy. Singing and laughing, he cried, “I had a dream. I passed the exam.” The next day, he disappeared.

The scholar took away with him his dream. The villagers felt miserable about his sudden departure, but it also gave rise to a strong desire. How nice, they thought, would it be if we had our own scholar to serve the village?

Liberation in 1949 shed the light of hope, giving the children for the first time in the village’s history the opportunity to go to school. For over 30 years, however, only a dozen or so villagers were able to finish high school, and none of them found his way to college. Most villagers could barely read and write.

Li Kehui, head of the village, is a middle-aged man whose wrinkled face and slightly hunched back make him look older. Since 1978, he has helped fellow villagers beat poverty by planting fruit trees and opening a gold mine. Yet, sitting under the gingko trees, he was lost in thought. He felt something was missing in the village’s development.

Once, the village bought a machine for 8,000 yuan (US$1,500), but it did not work. They had been told that the equipment was of a new design and reliable quality,but in fact it was made in the 1940s and could not be repaired. Li and the villagers were crestfallen. Obviously, ignorance gets one nowhere. The incident rekindled the 400-year-old dream that originated under the gingko trees.

Li gathered the villagers in front of the old machine and told them the legend again. He reminded them that over the past 30 years, Dayuancun had not produced a single scholar. He told them that without technology and knowledge it was impossible to develop the economy and improve the livelihood. At the meeting they decided that the first thing to do was to teach people in their 40s and 50s how to read and write while focusing on the education of children and teenagers. Four rules were set: first, the village would pay students all the way through junior high school; second, every polytechnic school student was entitled to a 200-yuan annual allowance and every college student was to receive 300 yuan every year; third, a teacher would get a 1,000-yuan bonus if he brought up a student who is enrolled in a key high school; and fourth, villagers had the right to dismiss any village leader who did not care about education.

Buddhist statues used to be ubiquitous in the village. Whenever a festival drew near, villagers would burn joss sticks in front of them. But now they started to “worship” teachers.

For over 30 years, Chen Wenliang, a local teacher, had been making the rounds of several villages on his old bicycle, tutoring local students. Li Kehui, feeling sorry whenever he saw Chen toiling on the bumpy mountain paths, decided to buy him a motorcycle at the village's expense.

Li himself pushed the motorcycle all the way to Chen’s home as he did not know how to ride it. Chen burst into tears as he accepted Li's expensive gift. “I will die an uneasy death if I fail to send any student for your village to college,” he said.

Before long, primary school pupils from Dayuancun village reported the best record in the whole township in the final examinations.

Upon learning that the township had decided that classes scattered in seven villages should merge into a key elementary school, Li talked the township leadership into building the school in Dayuancun. He promised that the village would foot all the bills for the construction of the school.

However, 110,000 yuan (US$20,000) was needed, which was no small sum for the village. A meeting was called under the gingko trees. Village head Li told participants that the poorer one was, the less he wanted to learn, and the less he learned, the poorer he became. “Without education, we can never get rid of poverty,” he said. Hardly had he finished his speech when a consensus was reached.

A third of a hectare of land under the gingko trees was set aside for the school. Several old people, eager to see the village dream come true, contributed wood they had kept for making coffins. In no time, a 15-room school sprang up, with its new desks, playground and flower beds. The voice of children reading and singing echoed under the old gingko trees.

The 400-year-old dream eventually becomes a reality. In 1982, Li Hongfeng, a young Dayuancun villager, was admitted into the Harbin Polytechnic University, thus becoming the first college student from the village. The admission meant so much to him. After his father’s death, the family had been in financial difficulties, and he had thought of dropping out. It was the village and his neighbours that provided him with the money and helped his family take care of the crops. Before the college entrance examinations, they even got him a tutor.

The admission letter in hand, the village head cried with joy. Scampering around the gingko trees, he could not help crying, “We have a college student at last.”

Dayuancun is accustomed to private celebration if a family has a elementary or high school student. But that time, almost every household in the village celebrated.

By 1986, ten youngsters from Dayuancun’s 200 households entered colleges in Beijing, Guangzhou, Shenyang, Kunming and other cities. Each of them got 300 yuan annually from the village plus travelling expense for summer and winter vacations. Their parents also enjoyed special care at home.

But would these students return after graduation? Li Kehui answered that it would be unlikely in the immediate future because the state now badly needed them. Sooner or later, though, some of them would come to work for the village.

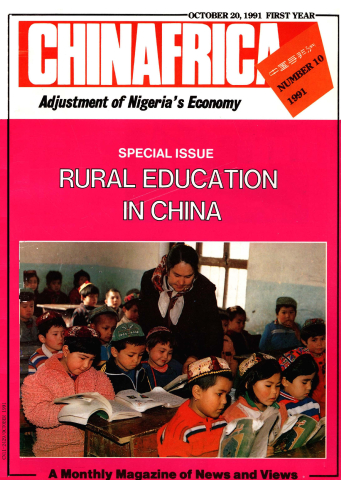

In the spring of 1987, another new building was completed near the gingko trees to house the village’s kindergarten. The money had been saved for an office building but the villagers finally decided to spent it on the most necessary facility. Unlike their fathers and grandfathers, children of the village have a bright future—they can enter elementary school, high school and college when they grow up. Two or three decades later, more and more people from the village will become scholars. The old dream has become a reality.

THe Dayuancun Kindergarten. XU SHAOBO

The towering Gingko trees at Dayuancun. XU SHAOBO

Copy Reference

Copy Reference